We came across this article on The Hearing Journal’s website and wanted to share it with you.

If you talk to one of your older patients about their greatest fears, you are likely to find that loss of memory or cognitive awareness ranks close to the top of the list. Although we know that hearing loss leads to isolation and depression,1 the typical senior focuses on deficits that may lead to a loss of independence, such as mobility or cognitive deficits.2 In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the possible link between cognitive decline and hearing loss in older adults among scientists and clinicians.

Some of this interest resulted from studies that used data obtained from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA), which has been active since 1958 and provided a wealth of data on various conditions known to be affected by aging, including hearing and cognition. Investigations of this dataset have revealed that individuals with hearing loss experience a steeper decline in cognitive abilities as they age than individuals with normal hearing.3

The implications of this study are fairly obvious, and this and follow-up studies have triggered speculation that perhaps hearing aid use may improve or offset cognitive decline. In fact, some hearing aid companies have capitalized on the hearing-cognitive connection in their advertisements. Given seniors’ fears of losing cognitive ability, this line of marketing makes sense. An older adult may be reluctant to try hearing aids, but the potential for improved or maintained cognitive ability might be a significant motivating factor.

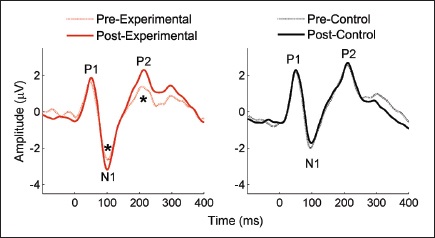

Figure 1.

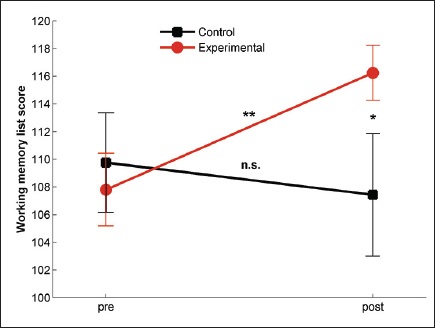

Figure 2.

EXAMINING THE EVIDENCE

Is there any evidence that hearing aid use improves cognitive ability? Recent studies have shown promising results. A 25-year longitudinal study showed that individuals with self-reported hearing loss experienced significantly more cognitive decline (measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination) than individuals with normal hearing.4 However, the hearing-impaired participants who wore hearing aids demonstrated cognitive ability similar to that of normal-hearing participants. Another study investigated several factors to determine if hearing aid use is associated with better cognitive performance.5 This study used the Digit Triple Test, a telephone speech-in-noise screening test that is highly correlated with audiometric thresholds,6 and measures of fluid intelligence, reaction time, and pairs matching (memory) to evaluate cognitive ability in a large cross-sectional sample of 164,700 participants.

They found that hearing aid use was associated with better cognition…

They found that hearing aid use was associated with better

Furthermore, while these studies show potential positive benefits of hearing aid use, it may be the case that individuals who have

To further explore these issues, we performed a short-term longitudinal study in new hearing aid users to determine if hearing aid use improves cognitive function. Because hearing loss and aging may affect cortical representation of auditory signals,8,9 we wanted to determine if hearing aid use results in changes in cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs) and whether neural changes are associated with cognitive improvements.

The study involved 36 participants with mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss who were randomly assigned to either the experimental (hearing aid use) or control (no hearing aid use) group. Eighteen participants in the experimental group and 14 participants in the control group completed the study. Each participant was fit with hearing aids (Widex Dream 440 receiver-in-the-canal hearing aids). CAEPs to the speech syllable /ga/ were recorded in aided and unaided conditions at the first visit and six months later. Cognitive testing (working memory,

The experimental group was instructed to wear the hearing aids for a minimum of eight hours per day. They were seen at regular intervals (two, six, 12, and 18 weeks) to ensure compliance with hearing aid use and to record aided CAEPs. During these visits, the participants’ data logging records were examined, and when necessary, they were counseled to troubleshoot reasons for non-use. The hearing aid settings were not adjusted until completion of the study.

STUDY RESULTS

We found that the amplitudes of the N1 and P2 cortical peaks increased after six months in the experimental group, but no changes occurred in the control group (Fig. 1). The two groups were matched in working memory at the first visit. After six months, the working memory standard score increased by an average of six points in the experimental group, but the working memory score did not change in the control group (Fig. 2). No changes in processing speed or attention/inhibition were seen in either group. Interestingly, increases in cortical P2 amplitudes related to improvement in working memory scores.

Previous studies have shown that sensory exposure may increase P2 amplitudes and thus improve the auditory system’s sound identification.10 Therefore, the association between cortical and working memory changes suggests that improved auditory perception frees up resources that can then be allocated to cognitive tasks, such as working memory.

We are currently evaluating the data to determine the time course of neuroplasticity. Knowledge of the time course of changes in neural and cognitive functions would provide an important counseling tool, especially for new hearing aid users.

While the results of this study are quite encouraging, it is important to note the limitations of the study. The control group did not receive any treatment and was not seen in the intervening months between the first and last visits. Therefore, their expectations for improvement would be reduced compared with the experimental group, possibly influencing performance during the final visit.

Also, this was a relatively small study, and it would be important to replicate these findings in a larger dataset. Finally, it would be beneficial to evaluate neuroplasticity in hearing aid users over a longer period using a double-blind protocol.

Acknowledgments: This study was supported by the Hearing Health Foundation and Widex USA (contributed hearing aids and funds). The Planning and Budgeting Committee for Higher Education in Israel and the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (R21DC015843, awarded to S.A.) also supported the study through funds to support H.K.’s postdoctoral fellowship.Back to Top | Article Outline

REFERENCES

1. Heine C, Browning CJ Communication and psychosocial consequences of sensory loss in older adults: overview and rehabilitation directions Disabil Rehabil 2002 24 15 763–773

2. Gopinath B, Schneider J, McMahon CM, Teber E, Leeder SR, Mitchell P Severity of age-related hearing loss is associated with impaired activities of daily living Age Ageing 2012 41 2 195–200

3. Lin F, Yaffe K, Xia J Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults JAMA Intern Med 2013 173 4 293–299

4. Amieva H, Ouvrard C, Giulioli C, Meillon C, Rullier L, Dartigues J-F Self-Reported Hearing Loss, Hearing Aids, and Cognitive Decline in Elderly Adults: A 25-Year Study J Am Geriatr Soc 2015 63 10 2099–2104

5. Dawes P, Emsley R, Cruickshanks KJ, et al Hearing Loss and Cognition: The Role of Hearing Aids, Social Isolation and Depression. PLOS ONE 2015 10 3 e01196166. Smits C, Kapteyn TS, Houtgast T Development and validation of an automatic speech-in-noise screening test by telephone Int J Audiol 2004 43 1 15–28

7. Karawani H, Jenkins K, Anderson S Restoration of sensory input may improve cognitive and neural function. Neuropsychologia. 20188. Billings CJ, Penman TM, McMillan GP, Ellis EM Electrophysiology and perception of speech in noise in older listeners: Effects of hearing impairment and age Ear Hear 2015 36 6 710–722

9. Presacco A, Simon JZ, Anderson S Evidence of degraded representation of speech in noise, in the aging midbrain and cortex J Neurophysiol 2016 116 5 2346–2355

10. Tremblay KL, Ross B, Inoue K, McClannahan K, Collet G Is the auditory evoked P2 response a biomarker of learning? Front Syst Neurosci 2014 8 28Copyright © 2019 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.